Is mainstream medicine hyping osteoporosis to goose profits? I’m revisiting and updating a previous article (“Rethinking Osteoporosis”) with some new findings.

I’ve long argued that the way medicine has marketed osteoporosis is akin to how it has put cholesterol on the map. Fifty years ago, our grandparents didn’t know their lipid scores from their shoe sizes; nowadays, thanks to successful marketing, cholesterol, LDL and HDL are as much a part of our lives as our social security numbers.

The result has been a bonanza for the makers of cholesterol lowering drugs.

In a similar way, we’ve mainstreamed routine bone density screening, such that a majority of women—and some men—can now recite their T-scores.

The Sell Job

No doubt BigPharma and the medical device industry have done a great sell job with their “osteoporosis awareness” campaigns. Last year, I wrote:

“A recent TV ad for a new expensive osteoporosis drug, Evenity®, seeks to create the impression that women are fragile porcelain dolls, teetering on the brink of toppling and shattering.”

Fear is a strong motivator.

And thus, manufacturers of DEXA scanners, doctors and hospitals who screen with them, and drug companies that make osteoporosis medications, have enriched themselves.

Osteoporosis is Big Business

According to Cognitive Market Research, the global market for one popular category of osteoporosis drugs—bisphosphonates like Fosamax, Actonel and Boniva—was 4.125 billion dollars in 2024 and will expand at a compound annual growth rate of 4.30% from 2024 to 2031.

In 2022, the global market for Prolia, a newer, pricier osteoporosis drug, was valued at $2.9 billion dollars. By 2030, the global Prolia market is expected to reach $7.2 billion dollars. The retail price of Prolia, without insurance reimbursement or rebates, is $1,875.43 per injection, which must be administered every six months, sometimes indefinitely.

Screening is lucrative, too. The global DEXA market was expected to reach $1.2 billion by 2024. It’s projected to grow at a rate of 8% annually to reach a total of 1.57 billion dollars by 2029.

Out-of-pocket costs for a DEXA scan average around $719 without insurance, depending on the state, and $160 to $175 with insurance. Of course, Medicare picks up the tab after it kicks in for seniors, allowing scans every two years. The ultimate consequence of this government subsidy is that more people get put on drugs.

Moving the Goalposts

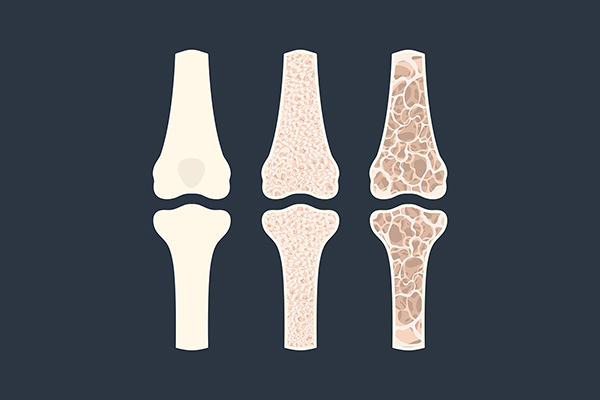

Based on DEXA scores, a study of postmenopausal women revealed 44.4% of those aged 56-60 had osteopenia, while 29.4% had osteoporosis. Osteopenia is an example of a “pre-disease”; only lately has diagnosis creep made persons with lower-than-optimal DEXA scores eligible for aggressive “preventive” treatment with drugs. The FDA-approved indications for bone-building medications do not specify osteopenia, which is a normal consequence of aging; they are reserved for outright osteoporosis, but doctors frequently overstep guidelines to prescribe drugs for run-of-the-mill osteopenia.

The Shortcomings of DEXA

What’s more, DEXAs render only a poor prediction of fracture risk. They measure bone density, but not bone quality; for example, a stick of blackboard chalk is denser than the supple trunk of a young sapling, but more likely to break.

Newer imaging techniques aim to assess whether bone tissue architecture is resistant to fracture, but they are experimental, not readily available, and poorly reimbursed. Given the slow pace of adoption of innovation in medicine, it’s unlikely they’ll be mainstreamed in the foreseeable future. I discuss some of the more promising candidate scans in a recent article (“We need better tests for osteoporosis”)

This is not to deny that debilitating fractures in older Americans take their toll. A broken hip in an eighty-year-old can be a death sentence.

Do the Benefits Warrant the Risks?

But is that all the screening, which inevitably leads to drug prescribing for individuals even with marginal declines in bone density, worth it?

As usual, one must weigh the benefits against the risks.

When it comes to the upside, the yield of screening healthy women at the time of menopause, as is now customary, is scant.

According to a recent U.S. Preventive Services Task Force report (“Screening for Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: A Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force”) published Feb. 11, 2025:

“ . . . the benefits of screening were seen only in high-risk women [older than] 65. The benefits of screening younger women at time of menopause, as reflected in a number-needed-to-treat analysis, were small.

There were only five to six fewer fractures per 1,000 women screened!

The USPSTF concluded:

“Risk assessment instruments, BMD alone, FRAX, or both have poor to modest discrimination for predicting fracture . . . Given these uncertainties, before ordering BMD tests in younger postmenopausal women, clinicians should counsel patients about the lack of evidence regarding benefits vs harms of initiating osteoporosis drug treatment at this life stage.”

Are Millions Being Needlessly Treated?

Most osteoporosis drugs have an unimpressive number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 100 to 200, meaning 99 to 199 women need to be treated unnecessarily to prevent a single hip fracture.

When it comes to preventing vertebral fractures, the drugs seem somewhat more effective, but a 2024 review in the American Journal of Medicine concluded “. . . whether these reductions correspond to less chronic pain and disability is unclear.”

Not that there isn’t a role for these drugs. Perhaps for a woman (or man) who has already had an osteoporotic fracture, a strong family history of premature osteoporosis, a severe digestive ailment like ulcerative colitis that interferes with nutrient absorption, early menopause, long-standing hyperparathyroidism, required hormone blockers for cancer, or taken bone-eroding steroid medication for years. The odds of preventing a subsequent fracture with drug therapy go up in such persons at serious risk—just as cholesterol-lowering drugs make most sense for those, not merely with high cholesterol, but with demonstrable plaque buildup.

No Free Ride

But what if osteoporosis medications were relatively free of side effects? Wouldn’t even the slight benefits they confer outweigh their negligible risk of harm? And shouldn’t they be initiated at the earliest possible age, before irreversible bone loss occurs?

Unfortunately, such is not the case. In my previous article I detailed that, in addition to their potential for weakening bone with long-term use, bisphosphonates—especially Fosamax—carry a substantial burden of mood effects. A Naturereview states:

“The use of alendronate [Fosamax] and other bisphosphonates has been associated with depressive symptoms in recent case reports . . . The reported risk of depressive ADRs [adverse drug reactions] was found to be over 14-fold greater in patients taking alendronate under the age of 65 and over fourfold greater for patients over 65 compared to the control.”

Breaking News About the Harms of Some Osteoporosis Drugs

Now comes word that another class of newer, pricier osteoporosis drugs may have serious adverse effects on the heart. While exonerating bisphosphonates of heart risks, a new study of nearly half a million patients found that Forteo users are 35% more likely to experience a heart attack; those prescribed Forteo or Prolia are 44% and 23% more likely, respectively, to experience atrial fibrillation.

These drugs have been on the market for years. During the safety trials required for their approval these side effects either did not emerge, or worse yet, were concealed.

This is a stark illustration of the trend for dire unforeseen harms to only emerge years, and sometimes decades, after thousands and sometimes millions of unsuspecting people have taken FDA-approved medications.

Alternatives to Bone Meds

What does work? Lifetime commitment to adequate dietary protein (bone is living tissue, not just a piggybank for calcium), resistance exercise to induce bone formation, balance training to avert falls—with the possible addition of bio-identical hormone replacement therapy to preserve bone after menopause, or to address low T in men.

(WARNING: Side effects may include improved cardiovascular and cognitive health, enhanced overall well-being, and extended longevity)

Supplements, too, can make a difference; visit my Osteoporosis Protocol here.

Improvements in diet during formative years to reduce inflammation’s impact on bone, along with early adherence to an active lifestyle to maximize bone reserve before bone begins its declines after the age of 30, would go a long way toward heading off late-life fracture risk.

BOTTOM LINE: Let’s reserve testing and medication for the small minority most likely to benefit and put fewer healthy persons on the osteoporosis conveyor belt.